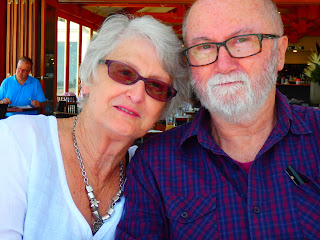

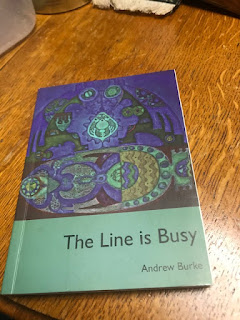

In 1950, Andrew Burke wrote his first poem – in chalk on a slate board. It was variations on the letter A. In 1958 he wrote a poem modeled on Milton’s sonnet on his blindness. Luckily it is lost. In 1960 he wrote a religious play about the Apostles during the time Jesus was in the tomb. It was applauded. He wrote some poems influenced by TSEliot and Gerard Manley Hopkins. They caused a rift in the teachers at the Jesuit school because they were in vers libre: the old priests hated them but the young novices loved them. It was his first controversy. (The only Australian poet in his school anthologies was Dorothea Mac kellor!) Around this time, Burke read the latest TIME magazine from USA. It had a lively article about the San Francisco Renaissance, quoting Lawrence Ferlinghetti who wrote: Priests are but the lamb chops of God. This appealed to Burke who became a weekend beatnik over night. When he left school, he hitch-hiked a la Kerouac across Australia to Sydney where he worked in factories, on trucks, at a rubbish dump and moving furniture. His poems appeared in these early days in Westerly, Nimrod, Overland and the Bulletin, and he returned to Perth to regain his health and joined a circle around Merv and Dorothy Hewett. A local poet William Grono hit the nail on the head when he described them as ‘I am London Magazine and you are Evergreen Review’. Long story short, Andrew Burke has written plays, short stories, a novel, book reviews and some journalism alongside a million advertisements and TV and radio commercials. He has also taught at various universities and writing centres and gained a PhD from Edith Cowan University in 2006 when he was teaching in the backblocks of China. As a poet he has published fourteen titles, one of the most popular being a bi-lingual published by Flying Islands Press in 2017, THE LINE IS BUSY (translated by Iris Fan). He is retired now but still writing and lending a hand to younger poets. A small selection of poems follow.

Going Home

As I exit, I walk by my books in the uni

library. There is a shorter way but I

choose to hear my old words whispering

off the shelf ‘in the swarm of human

speech’, as Duncan said. On my way home,

in the safe bubble of my Japanese car,

I take the tunnel and in the humming

dark inexplicably think of

my White Russian friend naked on

his chopper, whooping loudly in his flight

across the desert, ejaculating in ecstasy

on his fuel tank. Those were the days,

my friend. Now, my tunnel breaks

into sunlight. The poet I visited today said,

Even the poems are chatty now, and he

was right: at the red traffic light

lyrical lines come to mind and I hurry to

write them down. The lights change

and my pen dries out. Diesel fumes invade

my thoughts as I drive so I turn the volume

up on ABC Jazz to drown out my

annoyance. That motel has been there for decades.

I remember the one-eyed

mother, with her baby in a cot, offering

me her love, or something masquerading

as that, in dusky afternoon light, a room

rented after fleeing her husband, the sound

of peak hour traffic slowing as it banked

for the suburbs. I’m off in a dream world

when the car behind me toots, and I’m

on the road again. Her name has gone

but her eye patch remains and the baby’s

sweet snuffling. I change to a pop music

station. Get out of your own head, I

advise myself. It’s not safe there, the

past is corrosive. At home I park

and leave the bubble of car and poem

with its own centrifugal force.

Have a Nice Day

Driving to the shopping centre,

Bukovski rambling in my ear,

I’m glad to be sober

and anonymous. When I was

young, all hormones and energy,

my poetic was all about

getting laid. Today I step

from my Toyota, head full

of Buk, and grab a trolley, swearing

at its bent wheels. That’ll help,

my sober brain puts in, sarcastic

as ever. I push and the old desire

to be listened to comes back

and I’m impatient at each counter,

waiting for this, waiting for that.

They’ve got machines now,

not people. Just key in

your late mother’s hat size

and, voila, the money is out

of your account and into theirs,

Messrs Coles and Woolies. Warmly

I remember the décolletage of

Sandy with the metal in her nose,

tongue and ears. Where is she today?

At the scrap metal yard?

This machine doesn’t rock my world.

It doesn’t have Sandy’s knowing smile,

asking sweetly through banded teeth,

Any fly bys? It’s a drive-by, fly by,

bye-bye whirled. Who’ll enjoy

fly bys on my funeral plan?

Buk’s buggered my mood, but he’s

dead and I’m still here, so

who’s to complain. The machine

says, Have a nice day with

a metallic twang and I

kick the trolley straight again.

The limits of my language are the limits of my world. Wittgenstein

As bit players, the limits

of everyday activity

are the limits of our lives. You are

half out the door, going

who knows where. Perhaps you can

tell us when we meet again.

We don’t expect cards or letters,

emails or texts, and only our

limited senses would ask for

photos of the other side.

Did you leave your watch behind?

I picture Sue running

after you, shouting, ‘You forgot

your watch, you forgot your watch.’

Time is only for us now,

empty arms of the clock

hold us back from joining you.

When you were sick

and tired of it all, you left. I can

understand that. Mind the step,

wipe your feet. I expect we will follow you

in time. They chisel years

on tombstones, don’t they, yet facts

are putty in historians’ hands after deeds

are done. It’s a variety show, all this song and dance.

Total it up: More love than hate,

more laughter than tears. Do you need

a torch? Or is that light at the end of the tunnel

light enough? Perhaps you can send us

a clue or two, telling us, What happens next?

Eh? Tell me that.

Taibai Mountain Poem

for Jeanette

I saw a shining moon last night

through leafy poplars and pines

on Taibai Mountain

and thought of you awake

amid the lowing of Brahman bulls.

I thought of Li Bai

spilling ink down the mountain

leaving black stains

and wondered whose Dreaming

spilt red on The Kimberley?

None So Raw As This Our Land

for Mary Maclean

Many have been more exotic places, but this

you offer us, a taste of our land. The air

so crisp with chill we wear entire wardrobes

like hunters’ furs—jeans over track pants,

footy socks, beanies, scarves. Mary’s roo dog

does our hunting: an emu caught at the throat,

plucked and thrown whole on a cooking fire,

smoke full of singed feathers and flesh

stings our noses. We wrestle with tin-canned

standards in words the wind blows away. Huddled

round campfires morning and night, we go where

the sun breaks through as day unrolls. Breakaways,

mulga bush, a never-used dam a hundred years old,

this place of bleached bones and broken glass

queries our presence, unwashed, awkward on

its unpaved ways. Marrakesh, Katmandu—tales

of former hikes, but none so raw as this our land.

Whose land? Our week is up; we take away

film rolls, rusted horse shoes, ochre rocks.