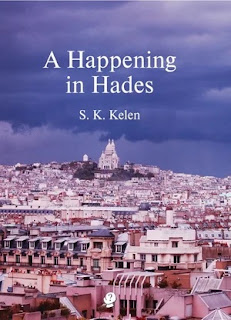

S. K. Kelen is an Australian poet who enjoys hanging around the house philosophically and travelling. His works have been widely published in journals, ezines and newspapers, anthologies and in his books. Kelen’s oeuvre covers a diverse range of styles and subjects, and includes pastorals, satires, sonnets, odes, narratives, haiku, epics, idylls, horror stories, sci-fi, allegories, prophecies, politics, history, love poems, portraits, travel poems, memory, people and places, meditations and ecstasies. A volume of his new and selected poems was published in 2012. His most recent book of poems, A Happening in Hades, was published by Puncher & Wattmann in 2020.

S. K. Kelen’s Flying Islands’ pocket book is Yonder Blue Wild (travel and places 1972 – 2017)

Three poems from Yonder Blue Wild:

Kambah Pool

A bend in the river, water’s clouded by green mud

Deep, really deep, good for proper swimming.

These days only children see spirit life

Work and play, see a world invisible to adults

Clear and just, a solar system glows every grain

Of sand and kids crush evil in one hand,

Until growing up evil comes again.

The light dappling the water surface

Reveals some native spirits’ power

Derives from fireflies. Gumnut babies

Fuss and fight give a lesson how funny

Is the futility of conflict. Children see

That crazy old spirit Pan left his shadow

Hanging from a tree and reflection

Drinking at the river, the old goat’s galloped

Way up mountain, leaps cliff to cliff

Grazes on blackberries growing in the scrub

Gazes over his Murrumbidgee domain.

All glands and rankness, his shaggy coat

Putrid with the smell of ewes, wallabies,

Kangaroos, still a monster, he’ll take

A bird bath later. Dirty musk fills the air

Like a native allergy, tea trees blossom

As he passes, kangaroos lift their heads

Breathe deep his scent and there are dogs, too.

When the kids see Pan they go gulp

If dads could see him they’d beat him to pulp.

You might not see but the musk stench

Wafts on the breeze. Currawongs squawk

The inside-out salute, warble a tone of pity

For the brute. The immigrant god moves inland—

Raucous the cockatoo never shuts up.

Letting Go

The train pulled into Madurai station early

in the morning. She stepped onto the platform

rubbed her eyes dazzled by the sunlight turning

the world white like a clean cotton sheet

she breathed deeply the morning’s incense

and thought it’s true you can smell India all the time.

The morning grew hotter and the light whiter

and the railway platform led to a street

made of dust compacted by a thousand years’

wheels, hooves and feet, the pavement

exploded with ramshackle stalls selling snacks

and bits and pieces, the lime painted buildings,

every now and then a garlanded Shiva or Ganesha.

(Brahmin cows strolled where they damn well pleased).

Thousands of people flowed out of houses

to join the crowd in the street all laughter

and gossip; children ran up hawking

gaudy drinks in plastic bags and paper cones

filled with nuts while old men sold boiled eggs

shouting that their eggs were the best eggs

and some beautiful women in beautiful saris

made tea and offered a cup for fifty rupee.

And in the corner of an eye: the urchins.

Lady Beggar stretched out her hand

breathed slowly a mute scream

performed the first asana from the book

of starvation yoga. Her eyes implored

yet mocked, her lips begged and sneered

her curving right arm pointed

to her mouth then her baby’s mouth,

pointed at her belly then her baby’s belly

she unleashed hunger’s slow ballet,

muttered soft pleas that hypnotised

and tugged the strings a good heart

holds in abundance (there are

many roads to heavenly realms,

not all pleasant). ‘Madam,’ she sang,

‘please madam, just a few pennies

and I can live a while—and my baby’

then the suburban woman’s eyes widened

as she emptied her purse of annas and cents

the beggar yelled delight

suddenly in the air there was a fragrance

like palm wine spilled on a balmy night.

A wild haired man with birds and insects

nesting in his elephantine legs

pointed at the mynah chicks chirping there

shouted ‘Benares! Benares!’

He received her fresh Indian banknotes

with laughing gratitude—

the next fifteen poor souls she gave

all her American dollars & pounds sterling.

The crowd of beggars grew.

Because they were hungry they laughed like crows—

she opened her suitcase and gave away her clothes

signed off the travellers cheques one by one, each

with a teardrop, threw away her camera like a bouquet

and bought every ragged child an ice cream.

The dusty streets are hot with the story.

A young girl asks ‘Can I have your earrings, madam?’

and is given them. A boy runs off with her laptop.

Then it is all white light then out of the light steps

a ragged King Neptune trident in hand

steps lightly through the crowd, waves the beggars on.

‘You are very kind madam those wretches

will live on your money like gods for a day or two

Your hand please — she stared at him and saw

his eyes not only held special intelligence

they reached into her. She came to

and grappled for her master card — lucky.

Her wide eyes narrowed and saw

no matter what she gave away she wouldn’t save

the world, it was weird what she had just done.

The sadhu’s eyes burned like suttee pyres, his muscles

tightened like ropes beneath the dusty rags—in another life

he’d have been a star or a psychopath—

here, he was a strange man in a strange land

He bowed nobly and hailed a taxi.

Megalong Valley

The gods banned machines from ever

entering the last pure tract of Megalong.

Here, even bracken’s picturesque

& the whipbird, breathless

with the beauty of it all,

is silent, reverential.

There’s a waterfall

splashing a rainbow

you walk under

that’s always there and will be

until the earth or sun shifts

sandstone cliffs, a kookaburra

laughs from gorgeous gloom

up & down, up & down.